Distributed Lock Pattern and Redis Implementation: A Complete Guide

In modern distributed systems, coordinating access to shared resources across multiple nodes is a fundamental challenge. The distributed lock pattern provides an elegant solution to prevent race conditions and ensure data consistency when multiple services need exclusive access to the same resource. This post explores the distributed lock pattern and dives deep into implementing it with Redis, one of the most popular choices for distributed locking.

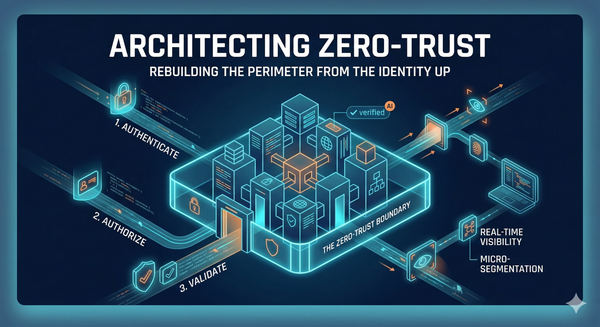

Understanding the Distributed Lock Pattern

A distributed lock is a synchronization mechanism that allows only one process or thread across multiple machines to access a shared resource at any given time. Unlike traditional locks that work within a single process or machine, distributed locks must coordinate across network boundaries, introducing unique challenges around network partitions, clock drift, and process failures.

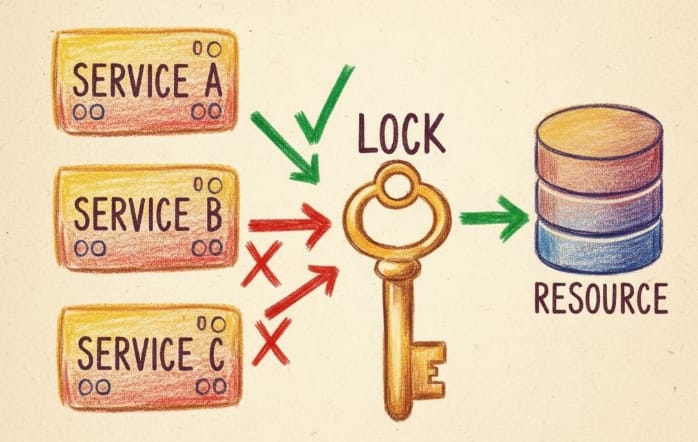

The core problem distributed locks solve is simple: when Service A in Tokyo and Service B in London both try to modify the same customer order simultaneously, how do we ensure only one succeeds at a time? Without proper coordination, both services might read the same initial state, make conflicting changes, and create data corruption.

The Anatomy of a Distributed Lock

A robust distributed lock implementation must satisfy several critical properties. Safety ensures that at any given moment, only one client can hold a lock. Liveness guarantees that the system can eventually acquire locks even when clients crash while holding them. Fault tolerance means the lock service continues operating despite individual node failures.

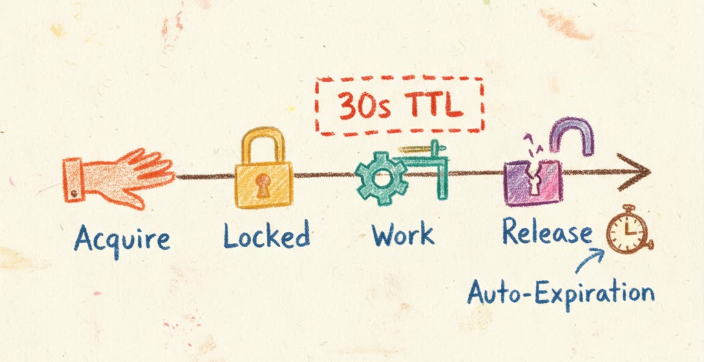

The typical lifecycle of a distributed lock follows a predictable pattern. A client attempts to acquire a lock by writing a unique identifier to a shared storage system with an expiration time. If the write succeeds and no other client holds the lock, acquisition succeeds. The client performs its critical operation, then explicitly releases the lock by deleting its identifier. If the client crashes, the lock automatically expires after a predetermined timeout, preventing permanent deadlocks.

Why Redis for Distributed Locks

Redis has emerged as a preferred choice for distributed locking due to its atomic operations, built-in expiration mechanisms, and exceptional performance. Redis operations like SET with the NX (not exists) and PX (expiration) options execute atomically, providing the foundation for safe lock acquisition. The in-memory architecture delivers sub-millisecond latency, crucial for high-throughput systems.

Redis supports several locking approaches, from simple single-instance locks suitable for non-critical scenarios to sophisticated multi-instance algorithms like Redlock for mission-critical applications. The simplicity of Redis commands makes implementation straightforward, while its Lua scripting capability enables complex atomic operations for lock release with ownership verification.

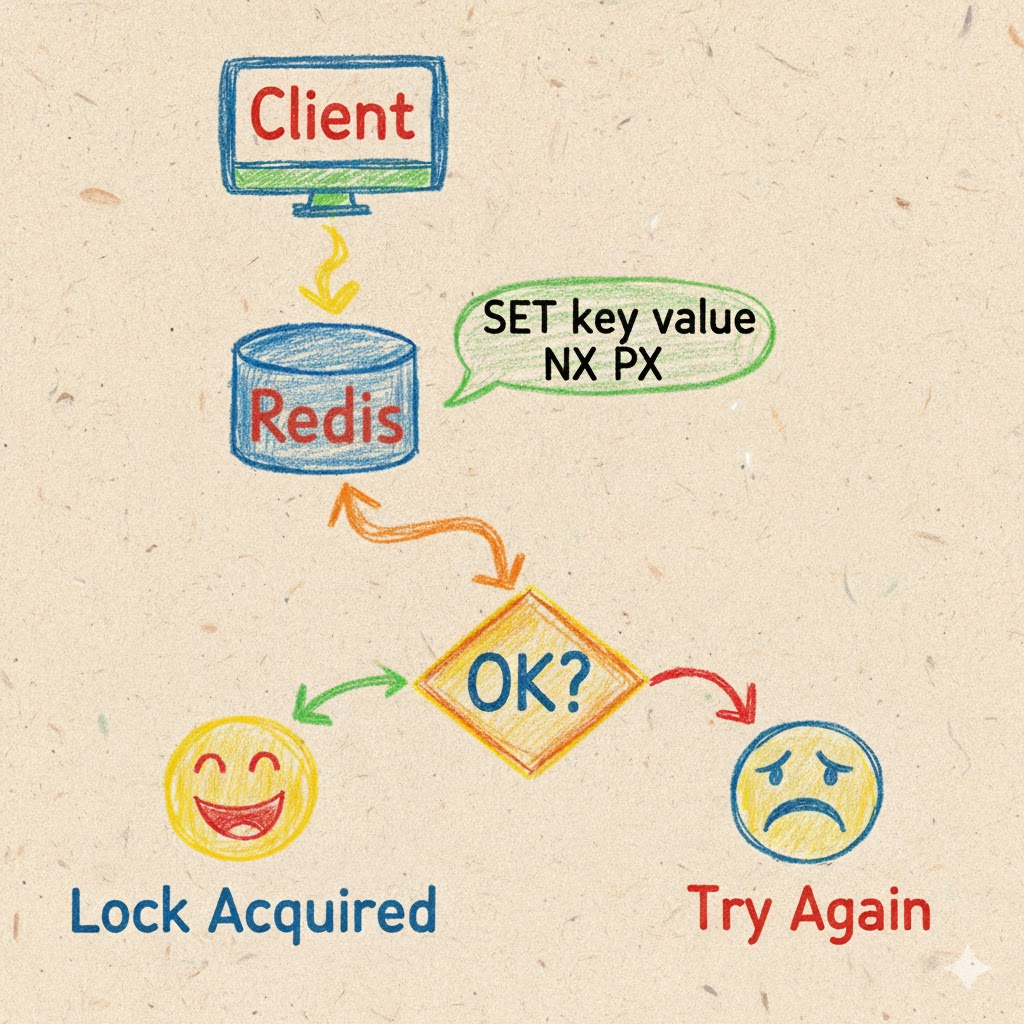

Implementing a Basic Redis Lock

The simplest Redis lock uses a single command combining multiple operations atomically:

SET resource_name my_random_value NX PX 30000

This command attempts to set a key called resource_name with a random value, but only if it doesn't already exist (NX), with an automatic expiration of 30 seconds (PX 30000). If the command returns OK, the lock is acquired. If it returns null, another client holds the lock.

The random value serves a critical purpose: ownership verification during release. When releasing the lock, the client must verify it still owns the lock before deleting it. This prevents a dangerous scenario where Client A's lock expires, Client B acquires it, and then Client A mistakenly deletes Client B's lock.

Safe lock release requires a Lua script that atomically checks ownership and deletes:

if redis.call("get", KEYS[1]) == ARGV[1] then

return redis.call("del", KEYS[1])

else

return 0

end

This script ensures the lock is only deleted if the stored value matches the client's unique identifier, maintaining the safety property.

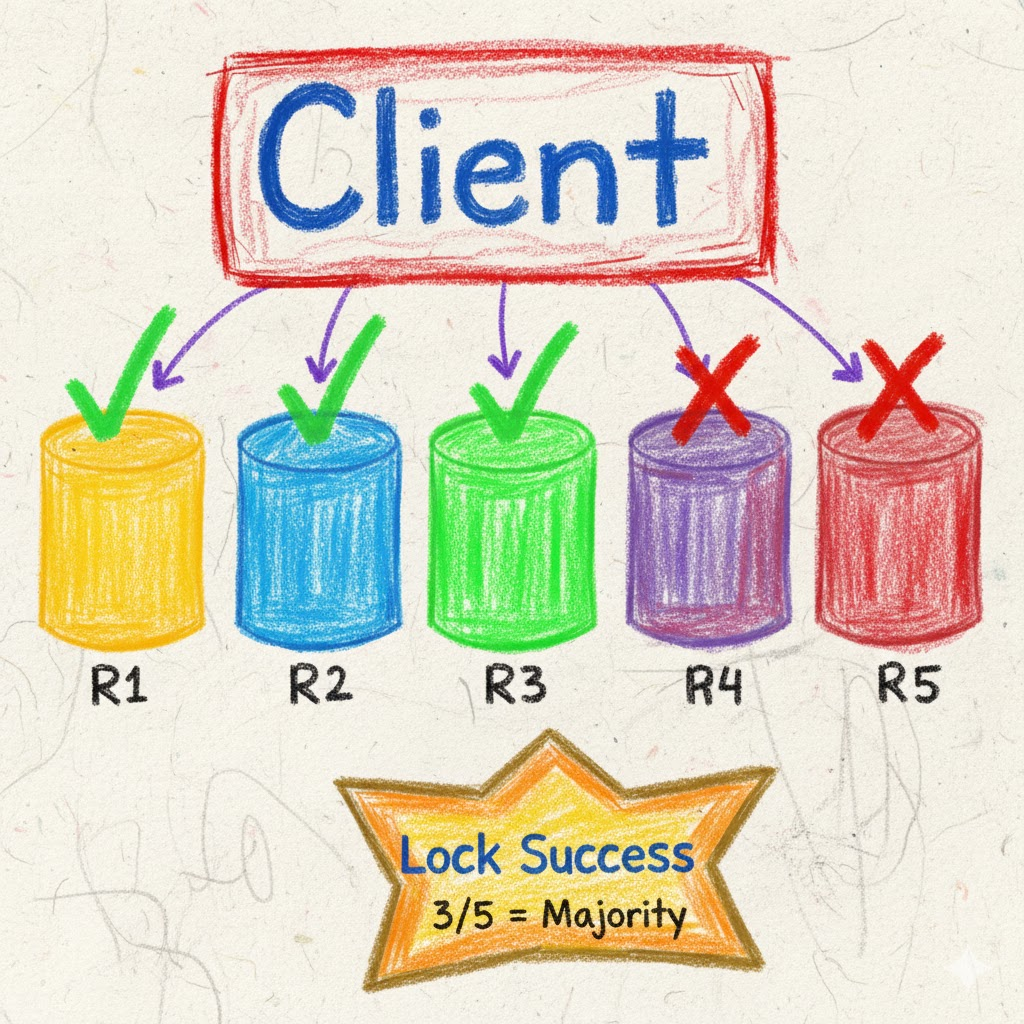

The Redlock Algorithm: Enterprise-Grade Locking

For production systems requiring the highest reliability, the Redlock algorithm extends the basic approach across multiple independent Redis instances. Instead of relying on a single Redis server, Redlock uses an odd number of completely independent Redis masters (typically 5) to achieve consensus.

The algorithm works by having the client attempt to acquire the lock on all N instances sequentially, using the same key name and random value, with a timeout much smaller than the lock's auto-release time. The client measures the total time elapsed during acquisition. If the client acquires the lock on the majority of instances (at least N/2 + 1) and the total acquisition time is less than the lock validity time, the lock is considered successfully acquired.

If the client fails to acquire the majority or exceeds the time limit, it releases all acquired locks on all instances, even those where acquisition failed. This prevents partial locks from lingering and causing availability issues.

The Redlock algorithm addresses several failure scenarios. If a Redis instance crashes after a client acquires a lock but before it expires, the remaining instances still maintain the majority consensus. Clock drift is mitigated by using short lock validity times and measuring elapsed time. Network partitions are handled by the majority requirement—at least three out of five instances must agree.

Real-World Use Cases

Distributed locks with Redis shine in numerous practical scenarios. Job scheduling in distributed task queues uses locks to ensure only one worker processes each job. When multiple workers monitor a queue, a distributed lock on the job ID prevents duplicate processing. The lock holder processes the job, and upon completion, releases the lock and removes the job from the queue.

Leader election in microservices often requires one instance to perform singleton tasks like database migrations or scheduled cleanup. Instances compete for a leadership lock with periodic renewal. The lock holder performs privileged operations while other instances remain on standby, ready to acquire the lock if the leader fails.

Inventory management in e-commerce prevents overselling by locking product SKUs during checkout. When a customer adds the last item to their cart, the checkout service acquires a lock on that SKU, verifies availability, decrements stock, and releases the lock. Without this lock, concurrent checkouts could sell the same item multiple times.

Rate limiting at the user level can use distributed locks to coordinate across API gateway instances. When enforcing "one request per user per second," the first gateway instance acquires a user-specific lock, processes the request, and holds the lock for one second. Other instances see the lock and reject concurrent requests from the same user.

Advantages of Redis Distributed Locks

Redis distributed locks offer compelling benefits that make them a popular choice. Performance is exceptional—Redis's in-memory architecture provides microsecond-level lock operations, supporting hundreds of thousands of lock acquisitions per second. This high throughput makes Redis suitable for latency-sensitive applications.

Simplicity is another major advantage. Implementing a basic distributed lock requires just a few Redis commands and minimal code. The learning curve is gentle, and debugging is straightforward with Redis's command-line tools providing visibility into lock state.

Flexibility allows tuning the tradeoff between consistency and availability. Single-instance locks offer maximum performance for non-critical scenarios, while Redlock provides stronger guarantees at the cost of complexity. Developers can choose the approach matching their requirements.

Built-in expiration eliminates the risk of permanent deadlocks. Even if a client crashes while holding a lock, the automatic timeout ensures other clients can eventually proceed. This self-healing property is crucial for system reliability.

Disadvantages and Limitations

Despite their benefits, Redis distributed locks have important limitations to consider. Single point of failure affects simple implementations using one Redis instance. If that instance crashes, the entire locking system becomes unavailable. While Redlock addresses this with multiple instances, it introduces operational complexity.

Clock drift can cause safety violations in edge cases. If a client acquires a lock with a 10-second timeout but its clock runs slow, it might hold the lock longer than intended, potentially overlapping with another client. While rare, this scenario requires careful timeout configuration.

Network partitions can lead to split-brain scenarios. If a client acquires a lock but then becomes network-partitioned from Redis, it thinks it holds the lock while other clients can acquire it after expiration. The client might perform operations assuming exclusive access when it's actually lost the lock.

Lock granularity tradeoffs require careful consideration. Fine-grained locks (one per resource) maximize concurrency but increase Redis memory usage and network overhead. Coarse-grained locks (one per resource group) reduce overhead but limit parallelism. Finding the right balance requires understanding access patterns.

Not a complete solution for all distributed coordination needs. Distributed locks handle mutual exclusion but don't solve leader election with metadata, distributed transactions, or consensus. For complex workflows, consider complementary tools like Apache ZooKeeper or etcd.

Best Practices and Architectural Insights

Successful distributed lock implementations follow several key principles. Always set expiration times to prevent deadlocks from crashed clients. The timeout should be at least 10x longer than the expected operation time, accounting for worst-case scenarios and network delays.

Use unique lock identifiers generated with UUIDs or similar mechanisms to prevent accidental lock release by other clients. Never use predictable values like node IDs or timestamps.

Implement retry logic with exponential backoff when acquisition fails. Busy-waiting with immediate retries wastes resources and can amplify contention. Waiting 100ms, then 200ms, then 400ms spreads out retry attempts and improves success rates.

Monitor lock metrics including acquisition latency, hold time, contention rate, and timeout occurrences. High contention suggests overly coarse lock granularity or the need for alternative coordination strategies. Frequent timeouts indicate operations taking longer than expected or crashed clients.

Consider lock-free alternatives for high-contention scenarios. If hundreds of clients compete for the same lock, the sequential bottleneck limits throughput regardless of Redis performance. Techniques like optimistic concurrency control, conflict-free replicated data types (CRDTs), or sharding can eliminate locking entirely for some use cases.

Plan for Redis failures with proper replication, persistence, and failover strategies. Redis Sentinel or Redis Cluster provide high availability, though they introduce additional complexity. Understand the consistency tradeoffs of each deployment mode.

Avoid holding locks during I/O operations when possible. If a client acquires a lock, makes a slow database query, processes results, and then releases the lock, it blocks all other clients unnecessarily. Consider splitting operations into lock acquisition for reading shared state, releasing the lock, performing computation, and reacquiring the lock for writing results.