Microservices and the Single Source of Truth: A Practical Guide to Data Ownership

In the world of distributed systems, one principle stands out as both foundational and frequently misunderstood: the Single Source of Truth (SSOT). When organizations transition from monolithic architectures to microservices, they often struggle with a deceptively simple question: "Who owns this data?" The answer to this question can make or break the success of a microservices architecture.

Understanding Single Source of Truth in Microservices

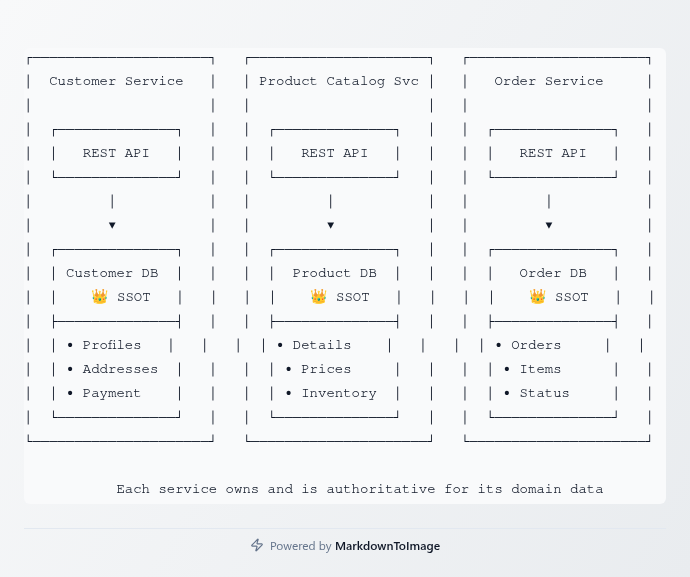

The Single Source of Truth principle states that every piece of data should have exactly one authoritative source. In a microservices architecture, this means each service should own and be the authority for its domain data. Other services that need this data should either query the owning service or maintain a read-only cache synchronized through events.

This concept might seem straightforward, but its implementation becomes complex when dealing with real-world business requirements. The challenge isn't just technical—it's about establishing clear boundaries, understanding data access patterns, and making intelligent trade-offs between consistency and availability.

Consider a typical e-commerce platform. Customer data lives in the Customer Service, product information in the Product Catalog Service, and order details in the Order Service. Each service is the single source of truth for its domain. When the Order Service needs customer information to process an order, it doesn't duplicate the entire customer database. Instead, it either queries the Customer Service or maintains a minimal cached copy of only the data it absolutely needs.

The Problem with Data Duplication

Before diving into solutions, it's worth understanding why data duplication in microservices causes problems. In a monolithic application, having redundant data across tables might be manageable—you can use database transactions to keep everything consistent. In a distributed system, this approach falls apart.

When multiple services maintain their own copies of the same data without a clear ownership model, several issues emerge. First, consistency becomes a nightmare. If the Customer Service updates an email address, how do you ensure all other services that cached this email get updated? What happens if one service is temporarily down during the update?

Second, the debugging experience deteriorates significantly. When a bug report comes in about incorrect customer data, which service's database do you trust? If three services have three different values for the same customer field, tracing the source of the discrepancy becomes an archaeological expedition.

Third, the cognitive load on the development team increases exponentially. Developers need to understand not just their service's data model, but also how their data relates to copies in other services, what synchronization mechanisms exist, and what happens when those mechanisms fail.

Establishing Data Ownership Boundaries

The first step in implementing SSOT is defining clear data ownership boundaries. This process requires understanding your domain model and business capabilities. Domain-Driven Design provides excellent guidance here—each bounded context should map to a microservice, and each microservice owns the data within its context.

Let's examine a user authentication and profile system. The Authentication Service owns credentials, security tokens, and authentication-related data. The User Profile Service owns profile information like preferences, bio, and profile pictures. The Notification Service owns notification preferences and delivery logs. Even though all three services deal with "user data," each owns a distinct slice with clear boundaries.

When establishing these boundaries, consider the business capability each service provides. The Authentication Service provides the capability to verify user identity. The User Profile Service provides the capability to manage user information. Each capability comes with its own data responsibility.

These boundaries aren't just technical divisions—they represent business concepts. When a new feature requirement comes in, the ownership boundary should make it immediately clear which service needs to implement it.

Access Patterns: Query vs. Event-Driven Synchronization

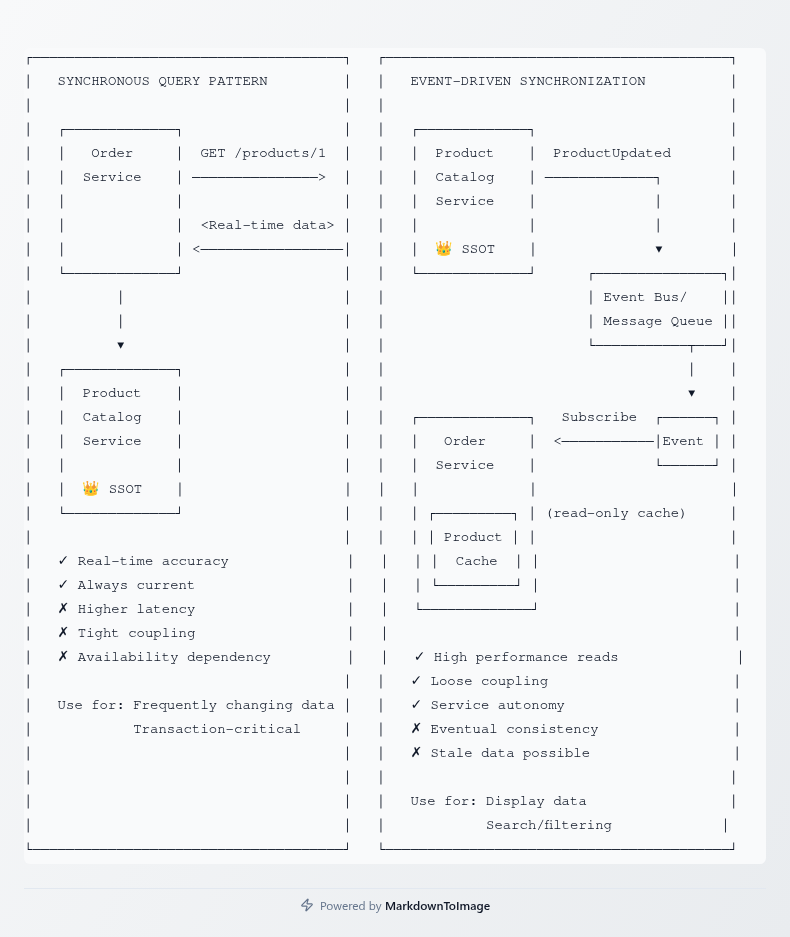

Once ownership is established, services need strategies to access data owned by others. Two primary patterns emerge: synchronous queries and event-driven synchronization.

Synchronous queries work well for data that changes frequently and requires real-time accuracy. When the Order Service needs to verify a product's current price, it queries the Product Catalog Service directly. This ensures the price used is always current. The trade-off is increased coupling and latency—the Order Service now depends on the Product Catalog Service being available and responsive.

Event-driven synchronization suits scenarios where eventual consistency is acceptable and read performance is critical. The Order Service might maintain a local cache of product names and basic information, updated through events published by the Product Catalog Service. When a product name changes, the catalog publishes an event, and the Order Service updates its cache. Orders can be displayed with product names instantly, without any cross-service calls.

The choice between these patterns depends on several factors. How often does the data change? What's the acceptable staleness for reads? What are the availability requirements? What's the performance budget for cross-service calls?

In practice, most systems use a hybrid approach. Critical data that directly impacts transaction outcomes is queried synchronously. Display data or information used for filtering and searching is cached locally and synchronized through events.

Handling Reference Data and Shared Concepts

Some data naturally needs to be referenced across multiple services. Customer IDs, product SKUs, order numbers—these identifiers appear in logs, databases, and API calls across the entire system. How do we handle these shared concepts while maintaining SSOT principles?

The key is distinguishing between the identifier and the data it represents. The Order Service can store a customer ID without storing customer data. It knows "this order belongs to customer 12345," but it doesn't claim to know the customer's name, email, or shipping address. When it needs that information, it queries the Customer Service using the ID.

This approach creates a reference without duplicating the source of truth. The Order Service owns the relationship ("this order belongs to this customer") while the Customer Service owns the customer details.

For truly shared reference data—like country codes, currency types, or category taxonomies—consider a dedicated Reference Data Service. This service becomes the SSOT for these shared concepts, providing a consistent vocabulary across all services.

Handling Data Aggregation and Reporting

One of the most challenging aspects of SSOT in microservices is aggregation and reporting. Business intelligence queries often need data from multiple services. A sales report might need customer demographics, product categories, order totals, and payment information—data owned by four different services.

Querying each service individually and joining the data in application code is rarely practical for complex reports. The solution is to separate operational data stores from analytical data stores. Each service remains the SSOT for its operational data, but an analytics database aggregates data from multiple services for reporting purposes.

This analytical database isn't a violation of SSOT—it's a read-only materialized view optimized for different access patterns. Data flows from the source-of-truth services to the analytics store through event streams or ETL processes. The services remain authoritative for writes; the analytics store provides efficient read access for complex queries.

Tools like Change Data Capture (CDC) can stream changes from operational databases to the analytics store with minimal impact on the source systems. The analytics store can then provide the fast, complex queries that business intelligence tools require.

Managing Data Consistency with Events

Event-driven architectures provide an elegant solution for maintaining consistency while preserving service autonomy. When the authoritative service changes data, it publishes an event. Other services that need to know about this change subscribe to these events and update their local caches or trigger their own processes.

This approach provides loose coupling—services communicate through events rather than direct calls. The publishing service doesn't need to know who's listening or what they'll do with the information. New services can subscribe to existing events without modifying the publisher.

However, event-driven consistency is eventual consistency. There's a lag between when the source of truth changes and when subscribers see that change. This lag might be milliseconds or seconds, depending on the event infrastructure. Applications must be designed to handle this temporary inconsistency.

Consider implementing idempotent event handlers to safely process duplicate events. Include versioning or timestamps in events to handle out-of-order delivery. Design UIs that acknowledge eventual consistency rather than misleading users about data freshness.

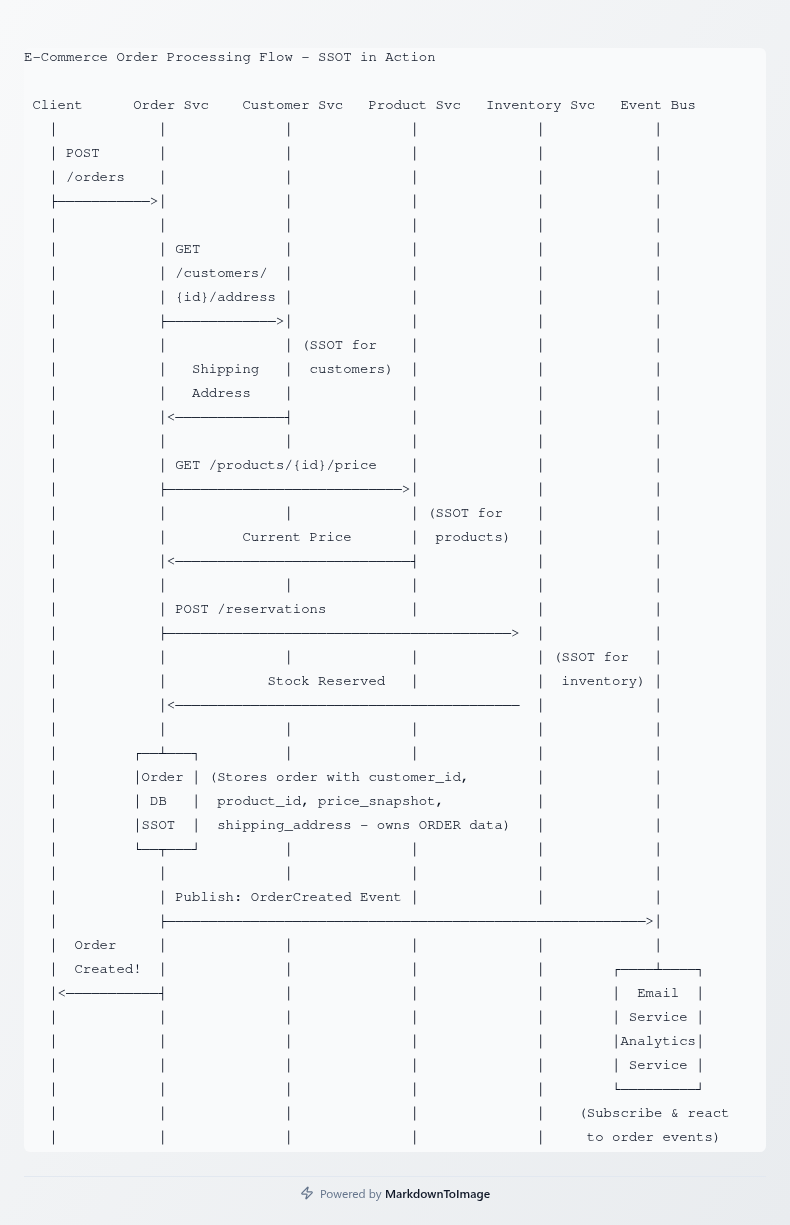

Real-World Implementation: E-Commerce Order Processing

Let's walk through a concrete example. An e-commerce platform processes an order that requires information from multiple services.

The Customer Service is the SSOT for customer data—name, email, shipping addresses, and payment methods. The Product Catalog Service owns product information—names, descriptions, prices, and inventory levels. The Inventory Service tracks stock levels and manages reservations. The Order Service owns orders and orchestrates the purchase process.

When a customer places an order, the Order Service creates an order record (it's the SSOT for orders). It queries the Product Catalog Service for current prices and product details. It calls the Inventory Service to reserve stock. It queries the Customer Service for the shipping address.

The Order Service stores the customer ID, product IDs, and the information needed to fulfill the order—quantities, prices at time of purchase, shipping address. It doesn't duplicate the current product price from the catalog (that might change), the current inventory level (irrelevant after reservation), or the customer's phone number (not needed for order fulfillment).

After the order is created, the Order Service publishes an "OrderCreated" event. The Email Service subscribes to this event and queries necessary services to send a confirmation email. The Analytics Service subscribes to aggregate order data for reports. Each service maintains its own source of truth while collaborating through well-defined interfaces.

Trade-offs and Practical Considerations

Implementing SSOT in microservices involves trade-offs. Strict adherence to SSOT principles can increase system complexity and latency. Sometimes, pragmatic duplication makes sense.

Caching frequently accessed, slowly changing data can dramatically improve performance. If product names change once a month but are read millions of times per day, caching them locally across services makes sense. The key is understanding that the cache isn't the source of truth and implementing proper invalidation strategies.

Another consideration is transactional boundaries. In a monolith, you might update customer information and create an order in a single transaction. With microservices and SSOT, these become separate operations. You might need to implement saga patterns or carefully design your processes to handle partial failures.

Network partitions and service failures add complexity. If the Customer Service is unavailable, can the Order Service still function? Perhaps it can process orders using cached customer data, with manual verification later. These decisions depend on business requirements and acceptable risk levels.

Anti-Patterns to Avoid

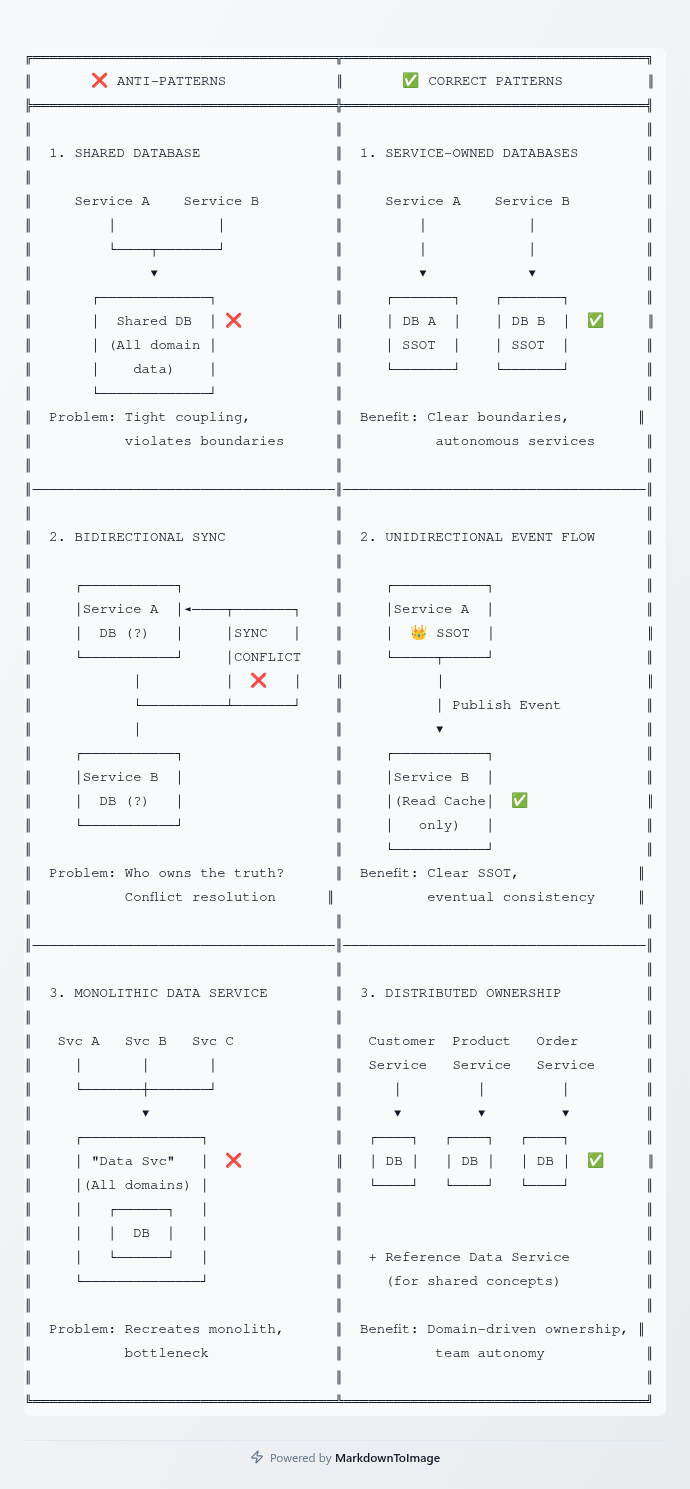

Several anti-patterns undermine the SSOT principle. The most common is the shared database anti-pattern, where multiple services directly access the same database. This creates tight coupling, makes schema evolution difficult, and violates service boundaries. Each service should own its data store.

Another anti-pattern is creating a "data service" that owns all data for all domains. This recreates a monolithic data layer and defeats the purpose of microservices. Data ownership should be distributed based on domain boundaries, not centralized.

The "bidirectional synchronization" anti-pattern occurs when two services both claim to own the same data and try to synchronize changes bidirectionally. This creates conflict resolution nightmares and ambiguity about the true source of truth. If two services need to update the same concept, that's a sign the domain boundaries need rethinking.

Advantages of Single Source of Truth

When implemented correctly, SSOT provides significant benefits. Data consistency becomes manageable because there's always a clear answer to "which value is correct?" Debugging is easier because there's one place to look for the authoritative data.

Service autonomy improves because each team owns their data completely. They can optimize their data model, choose appropriate database technology, and evolve their schema without coordinating with other teams. This autonomy enables faster development and deployment.

System scalability benefits because each service can scale its data store independently based on its own access patterns. The Product Catalog Service can use a read-optimized database with extensive caching, while the Order Service uses a write-optimized transactional database.

Challenges and How to Address Them

The primary challenge is managing distributed data access. Cross-service queries add latency and potential failure points. Mitigate this through strategic caching, asynchronous communication where possible, and careful API design.

Another challenge is maintaining referential integrity across services. Traditional foreign key constraints don't work across service boundaries. Address this through eventual consistency, compensating transactions, and acceptance that distributed systems have different consistency guarantees than monoliths.

Team communication becomes critical. Clear documentation of which service owns what data is essential. Service catalogs, API documentation, and architectural decision records help teams navigate the distributed data landscape.

Building for Evolution

Microservices architectures evolve. Initial domain boundaries might need adjustment as the business grows and understanding deepens. Design for this evolution by keeping service interfaces stable even as internal implementation changes.

Use API versioning to evolve interfaces without breaking clients. Publish data model changes through well-documented events. When domain boundaries need adjustment, plan careful migrations that maintain the SSOT principle throughout the transition.

Consider implementing a service mesh or API gateway that can route requests dynamically. This provides flexibility to refactor data ownership without changing client code.

Conclusion

The Single Source of Truth principle is fundamental to successful microservices architecture. It provides clarity, maintainability, and scalability while introducing complexity in distributed data access. The key is understanding when to strictly apply the principle and when pragmatic trade-offs make sense.

Start by establishing clear domain boundaries and data ownership. Choose appropriate access patterns based on consistency requirements and performance needs. Use events to maintain eventual consistency where acceptable. Build infrastructure to support aggregation and reporting without violating SSOT principles.

Most importantly, remember that microservices are about enabling organizational scalability and team autonomy. The SSOT principle supports these goals by giving each team clear ownership and responsibility for their domain data. When questions arise about data management, always return to this foundational principle: every piece of data should have exactly one authoritative source, and that source should be clear to everyone in the organization.