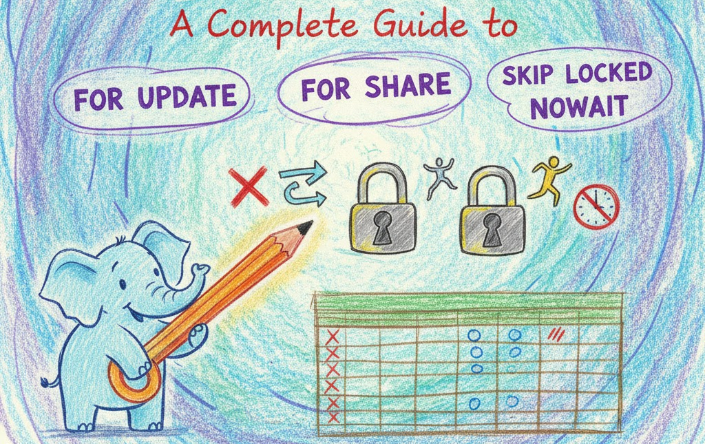

PostgreSQL Row-Level Locks: A Complete Guide to FOR UPDATE, FOR SHARE, SKIP LOCKED, and NOWAIT

Understanding PostgreSQL locking mechanisms is crucial for building concurrent, high-performance database applications. Row-level locks control how multiple transactions access and modify the same data simultaneously, preventing data corruption while maximizing throughput. This guide explores the essential PostgreSQL locking clauses—FOR UPDATE, FOR SHARE, SKIP LOCKED, and NOWAIT—and demonstrates when and how to use them effectively.

Understanding PostgreSQL Row-Level Locking

PostgreSQL implements Multi-Version Concurrency Control (MVCC) to handle concurrent transactions efficiently. However, certain operations require explicit row-level locks to ensure data consistency. When a SELECT statement includes locking clauses, PostgreSQL places locks on the retrieved rows, preventing other transactions from modifying or locking those rows until the current transaction completes.

Row-level locks become essential in scenarios where reading data and subsequently updating it must be atomic. Without proper locking, race conditions can occur where multiple transactions read the same data and attempt conflicting updates, leading to lost updates or inconsistent state.

FOR UPDATE: Exclusive Row Locking

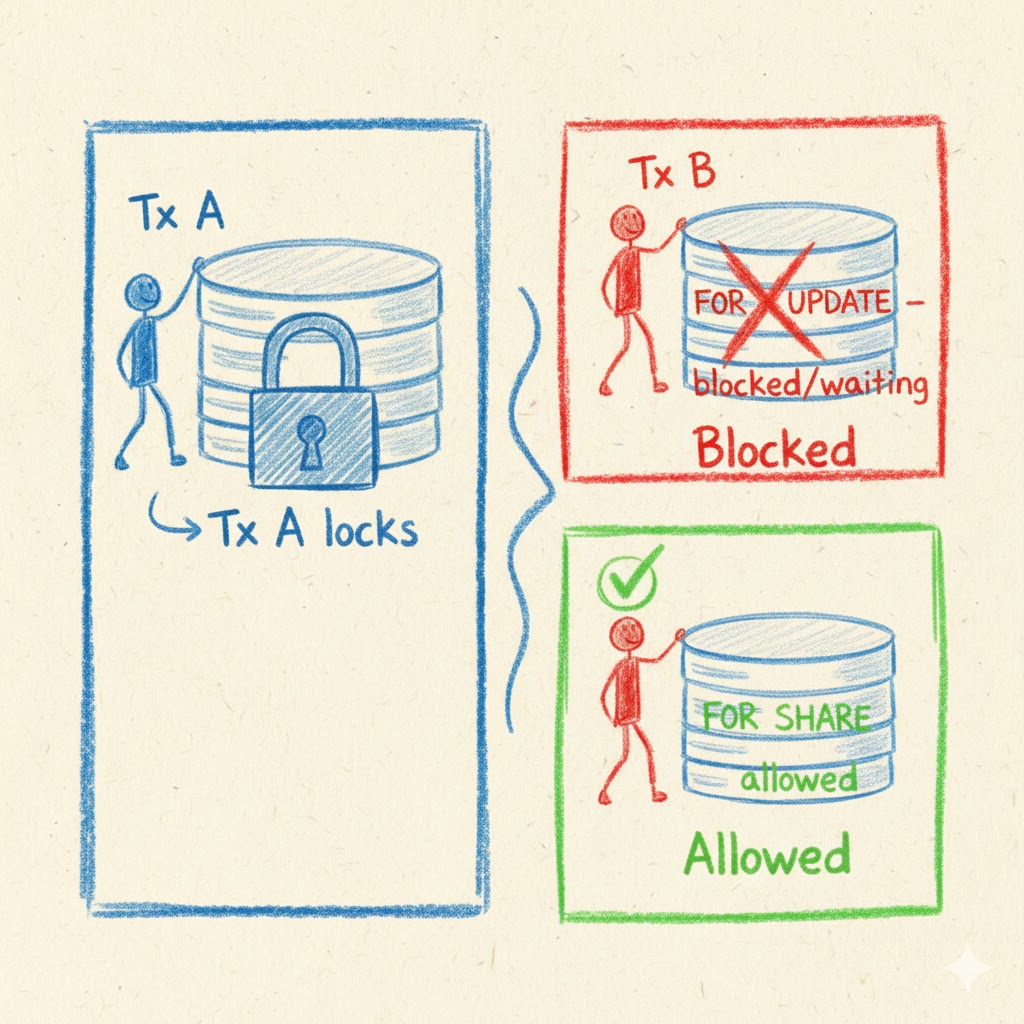

The FOR UPDATE clause acquires the strongest row-level lock in PostgreSQL. When a transaction executes SELECT ... FOR UPDATE, it locks the selected rows exclusively, preventing other transactions from updating, deleting, or locking those rows with FOR UPDATE or FOR SHARE.

BEGIN;

SELECT * FROM orders

WHERE status = 'pending'

AND user_id = 12345

FOR UPDATE;

-- Perform business logic and update

UPDATE orders SET status = 'processing' WHERE id = 98765;

COMMIT;

This pattern is ideal for scenarios requiring strict serialization, such as financial transactions, inventory management, or order processing systems. When transaction A holds a FOR UPDATE lock, transaction B attempting to acquire the same lock will wait until transaction A commits or rolls back.

The practical benefit emerges in e-commerce checkout flows. Imagine multiple users attempting to purchase the last item in stock. FOR UPDATE ensures only one transaction can claim the inventory, preventing overselling situations that plague poorly designed systems.

FOR SHARE: Shared Row Locking

FOR SHARE (also known as FOR KEY SHARE in newer PostgreSQL versions) provides a lighter-weight locking mechanism. Multiple transactions can simultaneously hold FOR SHARE locks on the same rows, but no transaction can modify those rows until all shared locks are released.

BEGIN;

SELECT * FROM products

WHERE category = 'electronics'

FOR SHARE;

-- Other transactions can read with FOR SHARE

-- but cannot UPDATE or DELETE these rows

COMMIT;

This locking mode suits read-heavy workloads where consistency matters but exclusive access isn't necessary. Multiple reporting queries can run concurrently with FOR SHARE locks, ensuring the underlying data doesn't change mid-analysis while allowing parallel execution.

Financial reporting systems often leverage FOR SHARE locks when generating month-end reports. Multiple report generators can read the same account records simultaneously, confident the data won't change, without blocking each other unnecessarily.

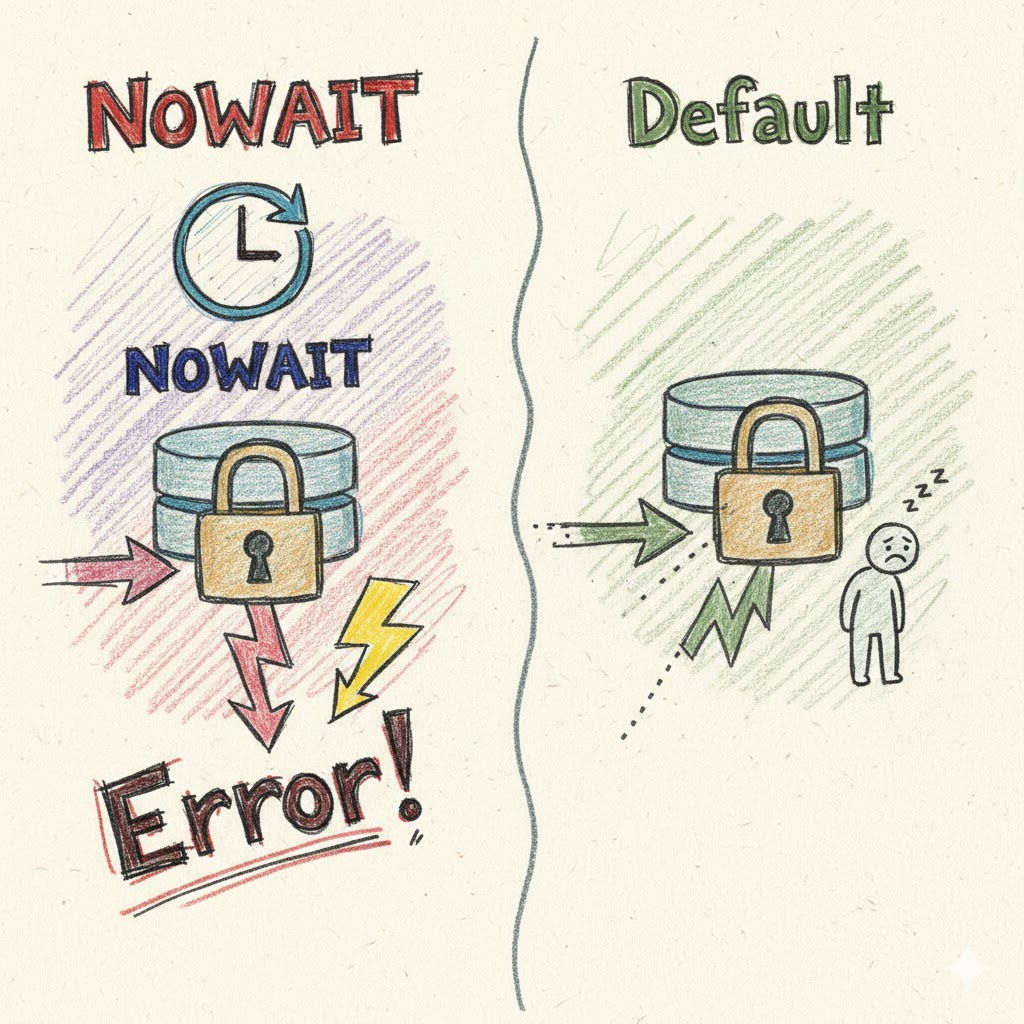

NOWAIT: Non-Blocking Lock Acquisition

By default, when PostgreSQL cannot immediately acquire a lock, the transaction waits indefinitely. The NOWAIT modifier changes this behavior dramatically, causing the query to fail immediately if locks cannot be acquired.

BEGIN;

SELECT * FROM inventory

WHERE product_id = 456

FOR UPDATE NOWAIT;

-- Raises error if row is already locked

COMMIT;

NOWAIT proves invaluable in user-facing applications where waiting indefinitely creates poor user experience. Rather than hanging the application, the transaction fails fast, allowing the application layer to display a friendly "resource busy" message or retry with exponential backoff.

High-frequency trading systems and real-time bidding platforms rely on NOWAIT to maintain responsiveness. If a transaction cannot immediately acquire necessary locks, it's better to abandon the operation and try the next opportunity rather than waiting and missing critical timing windows.

SKIP LOCKED: Processing Available Rows

SKIP LOCKED represents one of PostgreSQL's most powerful concurrency features, introduced in version 9.5. When combined with FOR UPDATE or FOR SHARE, SKIP LOCKED instructs PostgreSQL to ignore rows that are currently locked by other transactions, returning only unlocked rows.

BEGIN;

SELECT * FROM job_queue

WHERE status = 'pending'

ORDER BY created_at

LIMIT 10

FOR UPDATE SKIP LOCKED;

-- Process the jobs

UPDATE job_queue SET status = 'completed' WHERE id IN (...);

COMMIT;

This clause revolutionizes job queue implementations. Multiple worker processes can execute the same query simultaneously, each receiving a different subset of pending jobs without conflicts or waiting. Traditional queue systems required complex coordination mechanisms; SKIP LOCKED handles this elegantly at the database level.

Background job processors, email sending queues, image processing pipelines, and distributed task systems all benefit from SKIP LOCKED. The pattern scales horizontally—add more workers and they automatically distribute work without explicit coordination or message broker overhead.

Combining Lock Strategies: OF and Lock Strength

PostgreSQL allows fine-grained control over which tables in a JOIN receive locks using the OF clause. This specificity prevents over-locking and improves concurrency.

SELECT o.*, c.name, c.email

FROM orders o

JOIN customers c ON o.customer_id = c.id

WHERE o.status = 'pending'

FOR UPDATE OF o NOWAIT;

In this example, only the orders table receives the FOR UPDATE lock; the customers table remains unlocked. This distinction matters significantly in large applications where excessive locking cascades create bottlenecks.

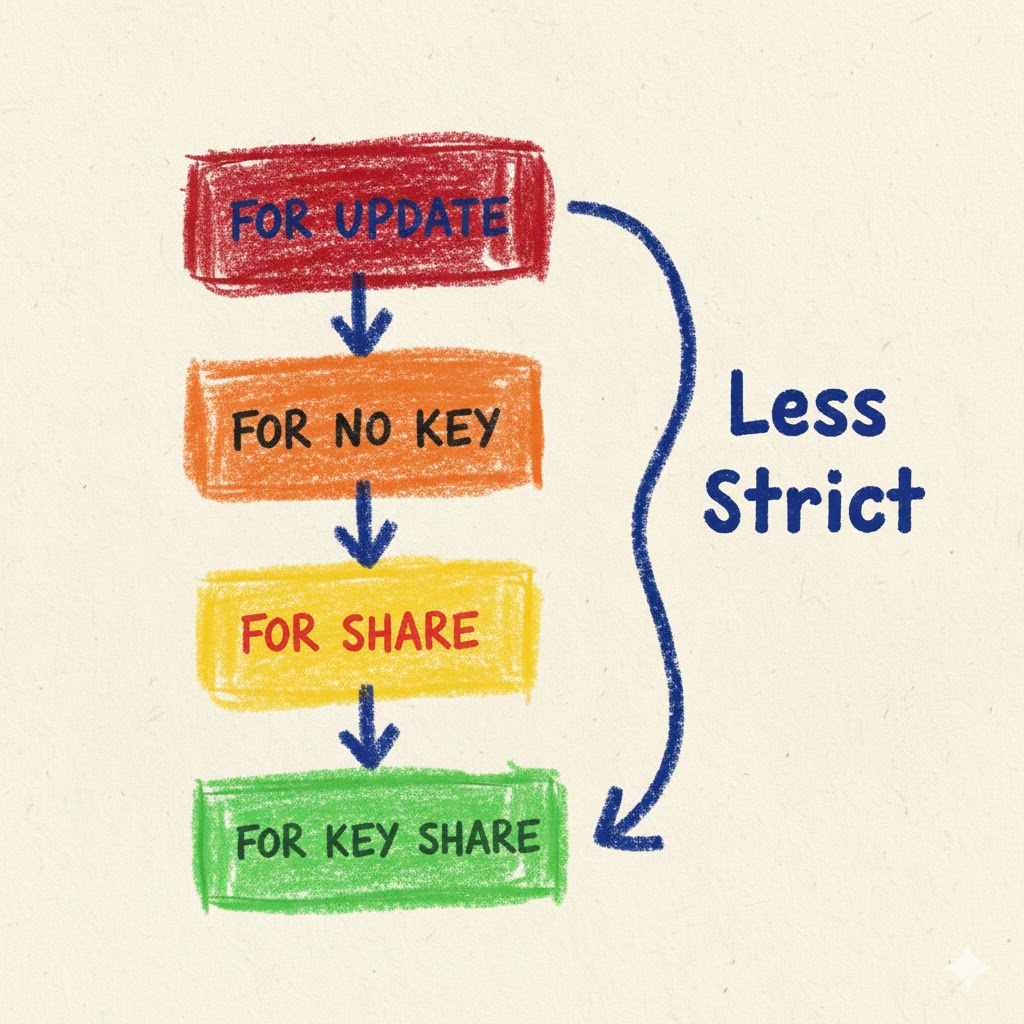

Lock strength hierarchy matters when mixing lock types. FOR UPDATE provides the strongest lock, followed by FOR NO KEY UPDATE, FOR SHARE, and FOR KEY SHARE. Understanding these levels helps optimize concurrency while maintaining necessary consistency guarantees.

Real-World Use Case: Building a Ticket Reservation System

Consider a concert ticket reservation system where thousands of users simultaneously attempt to purchase limited seats. The system must prevent double-booking while maintaining acceptable response times.

BEGIN;

-- Find available seats, skip those being reserved by others

SELECT * FROM seats

WHERE concert_id = 789

AND status = 'available'

ORDER BY section, row, number

LIMIT 5

FOR UPDATE SKIP LOCKED;

-- Reserve the seats

UPDATE seats

SET status = 'reserved',

reserved_by = 'user_12345',

reserved_at = NOW()

WHERE id IN (1001, 1002, 1003, 1004, 1005);

COMMIT;

This approach combines FOR UPDATE for exclusive access with SKIP LOCKED to avoid contention. Each user's transaction automatically selects different seats without coordination overhead. If seats aren't immediately available, the application can inform users or suggest alternatives rather than creating a waiting queue.

The pattern extends beyond ticketing to restaurant reservations, parking space allocation, resource scheduling, and any scenario requiring concurrent allocation from a limited pool.

Performance Considerations and Lock Monitoring

Lock contention directly impacts database performance. PostgreSQL provides system views to monitor lock activity and identify bottlenecks.

-- View current locks

SELECT

pid,

usename,

pg_blocking_pids(pid) as blocked_by,

query

FROM pg_stat_activity

WHERE cardinality(pg_blocking_pids(pid)) > 0;

Excessive lock waits often indicate application design issues rather than database problems. Solutions include reducing transaction duration, breaking large transactions into smaller units, or reconsidering whether strict locking is necessary.

Index design significantly affects locking performance. FOR UPDATE locks the entire row, but PostgreSQL must find those rows efficiently. Missing indexes force table scans, increasing lock duration and contention. Proper indexing on columns used in WHERE clauses with locking statements is essential.

Connection pooling behavior interacts with locking in subtle ways. Long-held locks combined with connection pool exhaustion can deadlock an entire application. Transaction-level pooling modes in PgBouncer help, but application logic must ensure transactions complete promptly.

Deadlock Detection and Prevention

Despite careful design, deadlocks can occur when two transactions acquire locks in different orders. PostgreSQL automatically detects deadlocks and aborts one transaction, allowing the other to proceed.

-- Transaction 1

BEGIN;

UPDATE accounts SET balance = balance - 100 WHERE id = 1;

UPDATE accounts SET balance = balance + 100 WHERE id = 2;

COMMIT;

-- Transaction 2 (executing simultaneously)

BEGIN;

UPDATE accounts SET balance = balance - 50 WHERE id = 2;

UPDATE accounts SET balance = balance + 50 WHERE id = 1;

COMMIT;

This classic deadlock scenario requires consistent lock ordering to prevent. Always acquire locks in a predictable sequence, typically by primary key order. Application-level coordination through ordered batch processing can eliminate many deadlock scenarios.

Setting reasonable deadlock_timeout values helps PostgreSQL detect and resolve deadlocks quickly. The default one second works well for most applications, but high-throughput systems may benefit from shorter timeouts.

Advanced Patterns: Lock Queues and Priority

While PostgreSQL doesn't natively support lock priorities, applications can implement priority queuing through careful lock acquisition strategies and timeout handling.

-- High-priority transaction with shorter timeout

SET LOCAL lock_timeout = '100ms';

BEGIN;

SELECT * FROM critical_resource FOR UPDATE NOWAIT;

-- Process high-priority work

COMMIT;

-- Low-priority transaction willing to wait

SET LOCAL lock_timeout = '5s';

BEGIN;

SELECT * FROM critical_resource FOR UPDATE;

-- Process background work

COMMIT;

This pattern allows time-sensitive operations to fail fast while background processes wait longer. Combined with application-level retry logic, it creates an effective priority system without custom database modifications.

Common Pitfalls and Anti-Patterns

Several locking anti-patterns plague PostgreSQL applications. The most common involves SELECT without locking followed by UPDATE based on the selected data. This race condition allows lost updates when multiple transactions read the same data before updating.

-- ANTI-PATTERN: Race condition

BEGIN;

SELECT balance FROM accounts WHERE id = 123;

-- Application logic calculates new balance

UPDATE accounts SET balance = 450 WHERE id = 123;

COMMIT;

-- CORRECT: Atomic read and update

BEGIN;

SELECT balance FROM accounts WHERE id = 123 FOR UPDATE;

-- Application logic calculates new balance

UPDATE accounts SET balance = 450 WHERE id = 123;

COMMIT;

Another pitfall involves holding locks during external operations like API calls or file I/O. Database locks should protect only database operations. Perform external work outside transactions or before acquiring locks.

Over-locking represents another common mistake. Not every SELECT requires FOR UPDATE. PostgreSQL's MVCC handles most read scenarios perfectly. Add explicit locks only when preventing concurrent modifications is essential for correctness.

Testing Locking Behavior

Properly testing concurrent behavior requires simulating simultaneous transactions. Tools like pgbench or custom test scripts using multiple database connections help validate locking logic.

-- Terminal 1

BEGIN;

SELECT * FROM products WHERE id = 100 FOR UPDATE;

-- Don't commit yet

-- Terminal 2

BEGIN;

SELECT * FROM products WHERE id = 100 FOR UPDATE NOWAIT;

-- Should fail immediately

-- Terminal 3

BEGIN;

SELECT * FROM products WHERE id = 100 FOR UPDATE SKIP LOCKED;

-- Should return empty result set

Automated testing frameworks can orchestrate these scenarios, ensuring locking behavior remains correct as the application evolves. Integration tests should explicitly verify that concurrent operations produce correct results without data corruption.

Choosing the Right Lock Strategy

Selecting appropriate locking mechanisms depends on specific requirements:

Use FOR UPDATE when exclusive access is mandatory, such as financial transactions, inventory updates, or state machine transitions where consistency is non-negotiable.

Use FOR SHARE when preventing modifications during complex reads matters, like generating consistent reports or validating relationships across multiple queries within a transaction.

Use NOWAIT when user experience demands immediate feedback and waiting is unacceptable. Interactive applications where users expect instant responses benefit from this approach.

Use SKIP LOCKED when processing work from a queue or allocating resources from a pool. This pattern enables efficient horizontal scaling without complex coordination.

Combining these strategies creates robust, performant systems. A job processing system might use FOR UPDATE SKIP LOCKED for workers claiming jobs and FOR SHARE for monitoring dashboards that display job status without interfering with processing.

Monitoring and Tuning Lock Performance

Production systems require ongoing lock performance monitoring. Key metrics include lock wait time, lock contention frequency, and deadlock occurrence rates.

-- Identify slow queries with lock waits

SELECT

calls,

mean_exec_time,

max_exec_time,

query

FROM pg_stat_statements

WHERE query LIKE '%FOR UPDATE%'

ORDER BY mean_exec_time DESC

LIMIT 20;

PostgreSQL's pg_stat_statements extension provides invaluable insights into query performance, including time spent waiting for locks. Enabling this extension in production environments is standard practice for performance-conscious teams.

Log settings like log_lock_waits help identify problematic lock contention. When enabled, PostgreSQL logs whenever a transaction waits longer than deadlock_timeout for a lock, providing visibility into contention hotspots.

Conclusion: Mastering PostgreSQL Concurrency

Understanding PostgreSQL row-level locking transforms how applications handle concurrent data access. FOR UPDATE provides exclusive access, FOR SHARE enables concurrent reads, NOWAIT prevents indefinite waiting, and SKIP LOCKED revolutionizes queue processing patterns.

Modern applications demand both consistency and performance. PostgreSQL's locking mechanisms deliver both when applied thoughtfully. The key lies in choosing appropriate lock types based on actual requirements rather than defaulting to the strongest locks or avoiding locking entirely.

Well-designed locking strategies enable applications to scale horizontally, processing thousands of concurrent transactions while maintaining data integrity. Whether building e-commerce platforms, financial systems, or high-throughput APIs, mastering these PostgreSQL features separates robust production systems from fragile prototypes.

The investment in understanding locking behavior pays dividends throughout an application's lifetime, reducing bugs, improving performance, and enabling confident scaling as user bases grow.

Keywords: PostgreSQL locking, FOR UPDATE, FOR SHARE, SKIP LOCKED, NOWAIT, row-level locks, database concurrency, PostgreSQL performance, transaction isolation, PostgreSQL MVCC, database locks, SELECT FOR UPDATE, concurrent transactions, PostgreSQL optimization, database race conditions, PostgreSQL deadlocks, job queue PostgreSQL, PostgreSQL SELECT SKIP LOCKED, PostgreSQL lock timeout, database transaction management