Understanding Transactions and Isolation Levels in PostgreSQL

When building applications that handle concurrent database access, understanding how PostgreSQL manages transactions and isolation levels becomes critical. These mechanisms determine how your application behaves when multiple users or processes access the same data simultaneously. Getting this right can mean the difference between a reliable system and one plagued by data inconsistencies.

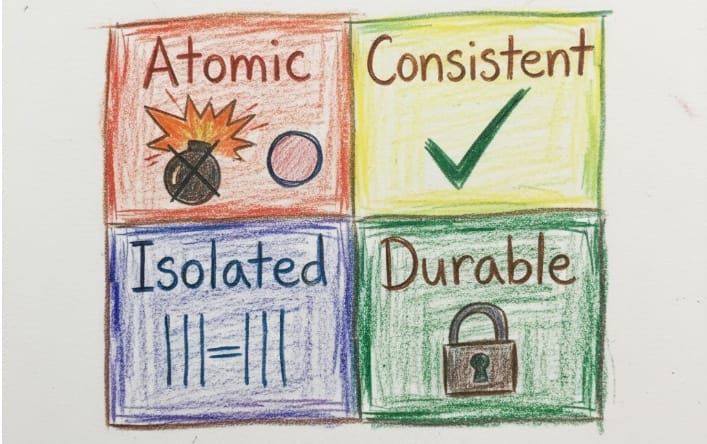

The Foundation: ACID Transactions

PostgreSQL transactions follow the ACID principles—Atomicity, Consistency, Isolation, and Durability. These aren't just academic concepts; they're practical guarantees that protect data integrity in production systems.

Atomicity ensures that all operations within a transaction either complete successfully or fail together. There's no middle ground where some changes persist while others don't. When a payment processing transaction updates both an account balance and a transaction log, atomicity guarantees that both updates happen or neither does.

Consistency maintains database invariants. If your schema enforces that account balances can't go negative, consistency ensures that no transaction can violate this rule, even temporarily within the transaction boundary.

Isolation is where things get interesting. It determines how concurrent transactions interact with each other and what intermediate states they can observe. This is the primary focus when discussing isolation levels.

Durability guarantees that once a transaction commits, its changes survive system crashes. PostgreSQL achieves this through Write-Ahead Logging (WAL), ensuring committed data persists even if the server crashes immediately after the commit.

Why Isolation Levels Matter

In a perfect world, every transaction would run in complete isolation, as if it were the only transaction executing on the database. But perfect isolation comes at a cost—performance. Higher isolation means more locking, more conflicts, and reduced concurrency.

The SQL standard defines four isolation levels, each offering different trade-offs between consistency guarantees and performance. PostgreSQL implements three of these (treating Read Uncommitted as Read Committed) with additional optimizations that make these levels more practical than the standard suggests.

PostgreSQL's Isolation Levels

Read Committed (Default)

Read Committed is PostgreSQL's default isolation level, and for good reason—it provides a sensible balance for most applications. In this mode, queries see only data committed before the query began. If another transaction commits while your transaction is running, subsequent queries within your transaction will see those new changes.

This behavior prevents dirty reads (seeing uncommitted changes from other transactions) but allows non-repeatable reads. If you read the same row twice within a transaction, you might get different results if another transaction modified and committed that row between your reads.

Consider an e-commerce inventory system. When a transaction checks if a product is in stock, then later performs the actual stock deduction, the stock level might have changed between these operations if another transaction completed a purchase. This is a non-repeatable read scenario that Read Committed allows.

For many applications, this is acceptable. Real-time systems often benefit from seeing the most recent committed data, even at the cost of some unpredictability. Banking systems displaying current account balances, social media feeds, and most CRUD applications work perfectly well at this level.

Repeatable Read

Stepping up to Repeatable Read provides a consistent snapshot of the database as it existed when the transaction started. All queries within the transaction see the same data, regardless of what other transactions commit during its execution.

PostgreSQL implements this through Multiversion Concurrency Control (MVCC), maintaining multiple versions of rows and showing each transaction the appropriate version based on its start time. This elegant approach avoids the heavy read locking that some databases employ for this isolation level.

The trade-off appears during writes. If two transactions running at Repeatable Read attempt to modify the same row, the second transaction to commit will fail with a serialization error. The application must be prepared to retry the transaction.

This isolation level shines in reporting systems where consistency across multiple queries matters more than seeing the absolute latest data. Financial reports, analytics dashboards, and batch processing jobs that require a stable view of data throughout their execution benefit significantly from Repeatable Read.

Serializable

Serializable is the strictest isolation level, guaranteeing that concurrent transactions produce the same result as if they had executed sequentially, one after another. PostgreSQL achieves this through Serializable Snapshot Isolation (SSI), a sophisticated algorithm that detects patterns of read-write dependencies that could lead to anomalies.

Rather than pessimistically locking everything (as older databases did), SSI allows transactions to proceed optimistically but monitors for dangerous patterns. When it detects a potential serialization anomaly, it aborts one of the conflicting transactions, which must be retried.

This approach makes Serializable surprisingly practical for many workloads. However, applications must implement robust retry logic because serialization failures become more frequent under high contention.

Use Serializable when correctness is paramount and the alternative would require complex application-level locking. Financial systems preventing double-spending, inventory systems preventing overselling, and any scenario where business logic demands that certain operations never interleave benefit from this level.

Common Concurrency Phenomena

Understanding what can go wrong helps clarify why different isolation levels exist.

Dirty reads occur when a transaction sees uncommitted changes from another transaction. PostgreSQL prevents these at all isolation levels, unlike some databases where Read Uncommitted allows them.

Non-repeatable reads happen when a transaction reads the same row twice and gets different results because another transaction modified the row in between. Read Committed allows this; Repeatable Read prevents it.

Phantom reads are trickier. A transaction executes the same query twice, but the second execution returns additional rows because another transaction inserted them. While the SQL standard allows phantoms at Repeatable Read, PostgreSQL's implementation prevents them through MVCC.

Serialization anomalies represent the most subtle issues—situations where concurrent transactions are individually valid but their interleaving produces results impossible in any sequential execution. Only Serializable prevents these.

Real-World Architectural Considerations

Choosing an isolation level isn't just a technical decision; it's an architectural one that affects system behavior and complexity.

Start with Read Committed for most applications. It provides good performance and prevents the most problematic inconsistencies. Only move to stricter levels when you have specific requirements.

Use Repeatable Read for complex business logic that spans multiple queries. If your transaction calculates something based on multiple reads, and those reads must be consistent with each other, Repeatable Read eliminates a class of bugs that would otherwise require careful application-level handling.

Reserve Serializable for critical operations where absolute correctness matters more than performance. The retry logic adds complexity, so apply it selectively to specific transactions rather than setting it database-wide.

Design for idempotency when using stricter isolation levels. Since transactions might be retried due to serialization failures, operations should be safe to execute multiple times. This is good practice anyway but becomes essential at Repeatable Read and Serializable.

Transaction Patterns and Best Practices

Keep transactions short. Long-running transactions at strict isolation levels hold snapshots open longer, increasing memory usage and making serialization conflicts more likely. Break large operations into smaller transactions when possible.

Use explicit locking sparingly. PostgreSQL's MVCC handles most concurrency needs without explicit locks. When you do need locks, understand the difference between FOR UPDATE (exclusive lock), FOR SHARE (shared lock), and their variants with SKIP LOCKED or NOWAIT modifiers.

Monitor for serialization failures in production. Applications using Repeatable Read or Serializable must handle and retry these failures. Track their frequency—if they're too common, you might need to redesign your transactions or reconsider your isolation level.

Consider SELECT ... FOR UPDATE at Read Committed as an alternative to stricter isolation. This pessimistic approach locks specific rows you intend to modify, preventing concurrent changes without affecting other data your transaction reads.

Performance Implications

Higher isolation levels aren't always slower. PostgreSQL's MVCC implementation makes Repeatable Read remarkably efficient for read-heavy workloads because it doesn't use read locks. You're essentially getting a free consistent snapshot.

The performance cost appears during conflicts. At Read Committed, concurrent updates queue but eventually proceed. At Repeatable Read or Serializable, conflicts cause transaction aborts that require retries, effectively doubling (or more) the work for those transactions.

Connection pooling and transaction management become more critical at stricter isolation levels. Each transaction holds resources, and serialization failures can cascade if not handled properly. Good monitoring and retry backoff strategies matter more as isolation strictness increases.

Making the Right Choice

The default Read Committed works well for the majority of applications. It provides intuitive behavior, good performance, and prevents serious consistency issues without requiring retry logic.

Move to Repeatable Read when you need consistent reads across multiple queries within a transaction. Reporting, analytics, and complex business logic often benefit from this guarantee. Just ensure your application handles serialization failures gracefully.

Choose Serializable only when you need absolute correctness guarantees that would otherwise require complex application-level locking. Financial systems, inventory management, and scenarios where races could cause significant business problems justify the additional complexity.

Conclusion

PostgreSQL's transaction isolation levels provide a spectrum of choices between performance and consistency guarantees. Understanding these options allows you to make informed architectural decisions rather than relying on defaults or folklore.

The key insight is that there's no universally "correct" isolation level. Read Committed serves most needs well. Repeatable Read provides stronger guarantees where needed without excessive overhead. Serializable offers perfect isolation for critical operations where correctness trumps convenience.

Design your transactions thoughtfully, measure their behavior in realistic conditions, and choose the isolation level that matches your actual requirements. Your future self—and your users—will appreciate the reliability and performance that comes from understanding these fundamental database concepts.