When One API Isn't Enough: Understanding the Backend for Frontend Pattern

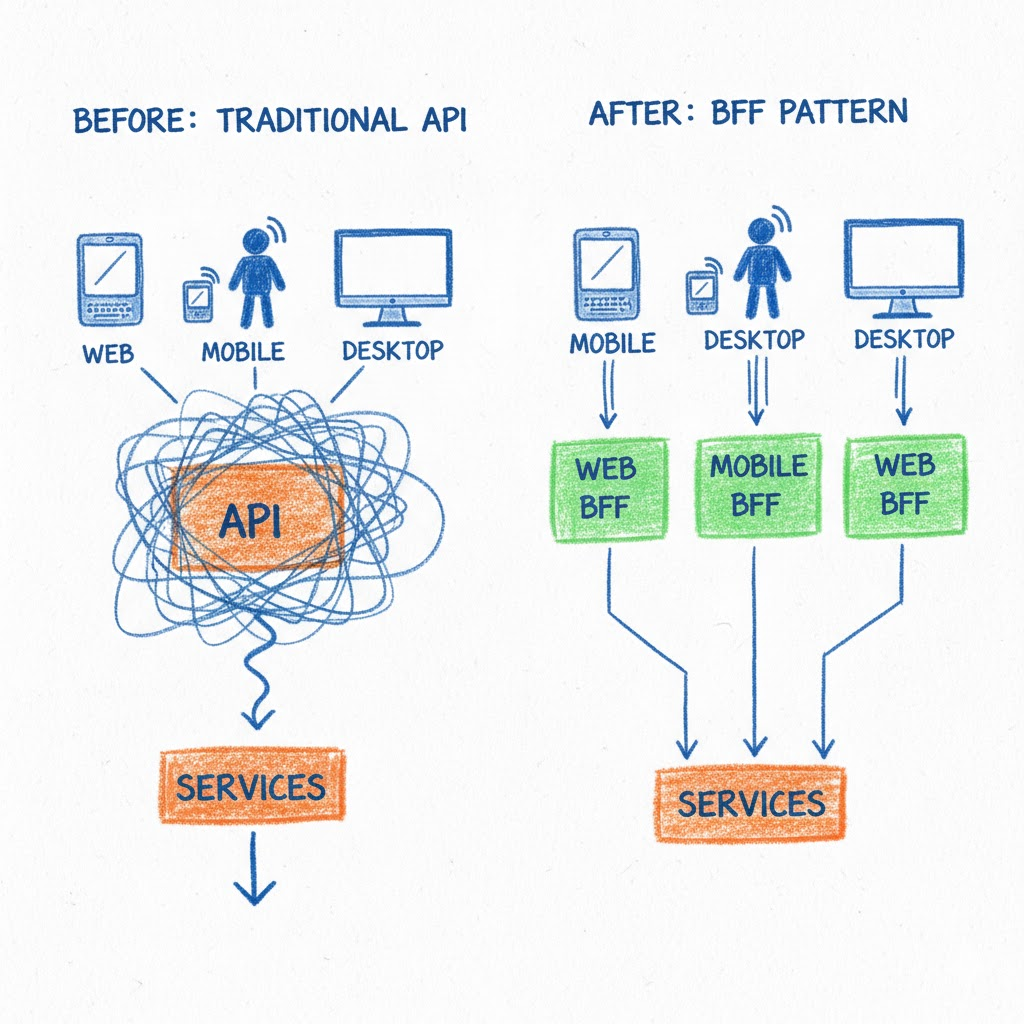

There's a common pattern that emerges in growing applications: what starts as a single, elegant API eventually becomes a tangled mess of optional parameters, conditional logic, and endpoints trying to serve too many masters. Web clients need different data than mobile apps. Third-party integrations require different authentication flows. The iOS team keeps asking for fields the web team doesn't need, and every change breaks something, somewhere.

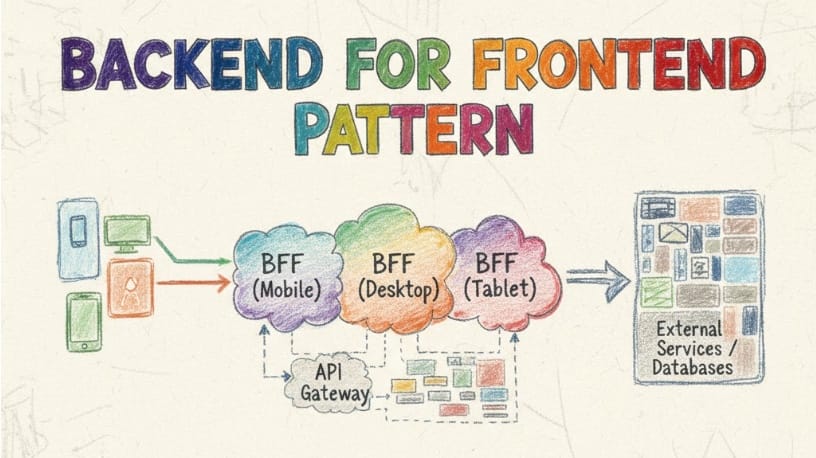

This is where the Backend for Frontend (BFF) pattern shines. Rather than forcing a single API to accommodate every client's unique needs, the BFF pattern suggests creating purpose-built backend services—one for each distinct user experience.

The Core Concept

The Backend for Frontend pattern, popularized by SoundCloud's Phil Calçado and later refined at companies like Netflix and Spotify, introduces a simple but powerful idea: place a specialized backend layer between each client application and your core services. Each BFF is owned by the team building that specific user experience, giving them the autonomy to shape their API exactly as needed without compromising other clients.

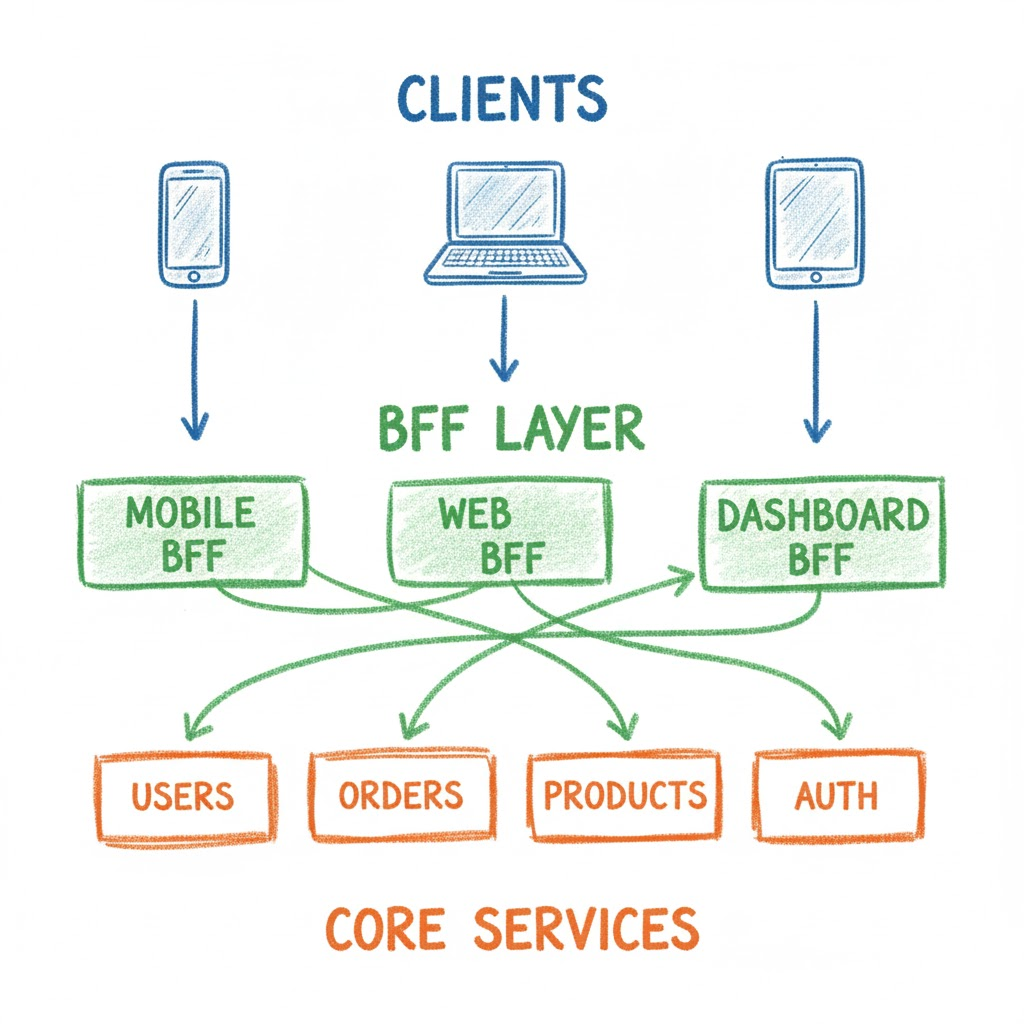

Think of it as a translation layer. Your web application gets a Web BFF that aggregates, transforms, and optimizes data specifically for browser consumption. Your iOS app gets a Mobile BFF tuned for mobile constraints—smaller payloads, offline considerations, and reduced chattiness. Your third-party API gets its own BFF with proper rate limiting, documentation, and stability guarantees.

Why This Pattern Emerged

The pain points that lead teams to adopt BFFs are remarkably consistent across companies and domains. As applications scale, a monolithic API accumulates technical debt in predictable ways.

Client-Specific Requirements Accumulate Mobile clients might need image URLs pre-signed for CDN delivery, while web clients handle this client-side. Native apps benefit from denormalized data structures to minimize round trips, while single-page applications prefer normalized data for efficient caching. Each special case adds conditional logic, query parameters, and complexity to shared endpoints.

Performance Characteristics Differ A desktop application on a stable broadband connection can handle verbose JSON responses with nested objects. A mobile app on a spotty 4G connection needs minimal payloads and aggressive caching strategies. Trying to optimize a single API for both scenarios leads to awkward compromises—either mobile gets bloated responses or web gets fragmented data requiring multiple requests.

Teams Step on Each Other's Toes When the mobile team needs to add a field, they must coordinate with API maintainers who worry about breaking web clients. When the web team wants to restructure response formats, they face pushback from mobile teams with different constraints. The shared API becomes a coordination bottleneck, slowing everyone down.

Security and Stability Requirements Diverge Internal dashboards might require elevated permissions and access to sensitive administrative data. Customer-facing mobile apps need strict rate limiting and defensive error handling. Third-party integrations demand stable contracts with versioning guarantees. A single API layer struggles to balance these competing concerns.

How BFFs Work in Practice

Implementing the BFF pattern requires rethinking how backend responsibilities are distributed. Rather than one team owning "the API," responsibility shifts toward the edges—closer to where user experience decisions are made.

Ownership and Autonomy Each BFF is owned by the team building that client experience. The iOS team owns the iOS BFF. The web team owns the Web BFF. This alignment is crucial—it means the people best positioned to understand performance requirements, data needs, and user experience concerns have direct control over the backend that serves them.

This ownership model eliminates the coordination tax. Need to add a new field? Update your BFF directly. Want to restructure how data is aggregated? Make the change without cross-team meetings. The BFF becomes an extension of the client application, deployable on the same cadence, using the same programming language if desired.

Aggregation and Transformation BFFs excel at orchestration. A typical BFF handles several key responsibilities:

The BFF aggregates data from multiple downstream services. When a mobile app requests a user profile, the Mobile BFF might call a User Service for account details, a Subscription Service for plan information, and a Content Service for viewing history—then stitch this together into a single, coherent response optimized for the mobile UI.

It transforms data into client-appropriate formats. Currency formatting, date localization, image URL construction, and computed fields can happen in the BFF rather than bloating core services with presentation logic. The same underlying product price might be formatted as "$1,299.99" for US web clients and "€1.199,99" for European mobile apps.

The BFF implements client-specific caching strategies. Mobile clients benefit from aggressive edge caching with long TTLs. Administrative dashboards need fresh data with short TTLs. Each BFF can implement caching policies aligned with its client's needs.

Technology Choices BFFs offer flexibility in technology selection. A Mobile BFF might use GraphQL to give iOS and Android developers precise control over data fetching. A Web BFF might use REST with server-side rendering to optimize initial page loads. An Internal Dashboard BFF might expose gRPC for efficient internal communication.

This heterogeneity is a feature, not a bug. Each BFF can adopt technologies that best serve its client, without forcing those choices on other teams.

When BFFs Make Sense

The BFF pattern isn't a universal solution—it introduces complexity that only pays off in specific contexts.

Multi-Platform Applications The pattern shines when maintaining distinct client applications with genuinely different needs. A company offering web, iOS, Android, and third-party API access will find BFFs natural. Each platform has unique constraints, performance characteristics, and update cycles that benefit from dedicated backends.

Client Teams with Backend Capabilities BFFs work best when client teams have the skills and mandate to own backend services. If "mobile developers" only write Swift and Kotlin, introducing Mobile BFFs requires hiring, training, or restructuring teams. The pattern assumes full-stack capability within client-focused teams.

Microservices Architectures BFFs pair naturally with microservices, where core domain logic lives in specialized services and BFFs handle cross-cutting concerns like aggregation and presentation. In monolithic architectures, the benefits are less clear—you might be better served by versioned endpoints or feature flags.

Rapid Client Evolution When client applications evolve quickly—new features weekly, design iterations constantly—BFFs provide the flexibility to change backend contracts without coordinating across teams. If your application is stable with infrequent updates, the overhead may not justify the benefits.

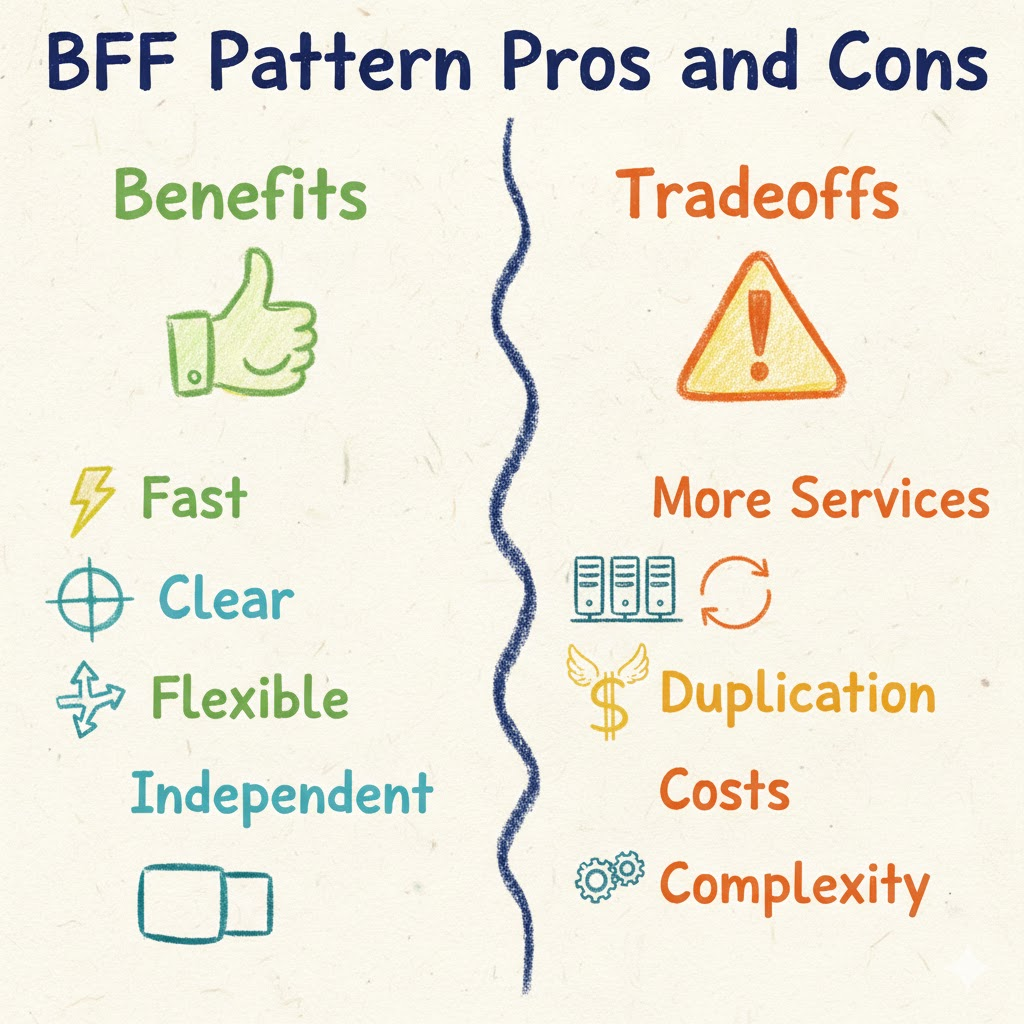

The Advantages

When implemented thoughtfully, BFFs deliver tangible benefits that justify their complexity.

Improved Performance Client-optimized APIs reduce over-fetching and under-fetching. Mobile BFFs can minimize payload sizes, decreasing bandwidth costs and improving load times on slow connections. Web BFFs can prefetch and denormalize data for optimal first-paint performance.

Clearer Boundaries Each BFF has a well-defined purpose: serve one client experience. This clarity reduces cognitive overhead and makes codebases easier to understand. New developers joining the iOS team can immediately identify where their backend logic lives.

Independent Deployment BFFs enable client teams to deploy backend changes independently. The web team can ship new features without waiting for mobile team approval. Deployment frequency increases, and coordination overhead decreases.

Technology Flexibility Different BFFs can adopt different technologies, programming languages, and architectural patterns. The Mobile BFF might use Kotlin and GraphQL. The Web BFF might use Node.js and REST. The Analytics BFF might use Python and batched exports. Each team optimizes for their use case.

Security Isolation Different clients can have different security postures. The Internal Admin BFF can access sensitive operations unavailable to customer-facing BFFs. Rate limiting, authentication mechanisms, and authorization policies can be tailored to each client's risk profile.

The Disadvantages

The BFF pattern introduces challenges that teams must actively manage.

Code Duplication Multiple BFFs often implement similar logic—validation, authentication, error handling, and common transformations. Without discipline, this duplication leads to inconsistency. One BFF might validate phone numbers strictly while another accepts any string. Shared libraries and code generation tools can help, but duplication remains a persistent challenge.

Operational Complexity Instead of operating one API service, teams now operate multiple BFF services. This multiplies infrastructure concerns: deployment pipelines, monitoring dashboards, error tracking, log aggregation, and on-call rotations. For small teams, this overhead can be overwhelming.

Coordination Still Required While BFFs reduce coordination at the API layer, coordination shifts elsewhere. Breaking changes in core services now impact multiple BFFs. Schema evolution, authentication protocols, and cross-cutting concerns still require alignment. The coordination tax decreases but doesn't disappear.

Resource Costs Running multiple BFF services increases infrastructure costs. Each BFF needs compute resources, load balancers, monitoring, and potentially separate databases for client-specific caching. These costs must be weighed against the benefits.

Team Structure Requirements BFFs work best with full-stack teams capable of owning both client and backend. Organizations structured around "backend teams" and "frontend teams" may struggle to adopt BFFs without reorganization. The pattern assumes organizational changes that may not be feasible.

Implementation Patterns and Anti-Patterns

Pattern: BFFs as Thin Orchestration Layers Keep BFFs focused on aggregation, transformation, and presentation logic. Business rules, data persistence, and domain logic belong in downstream services. A common guideline: if the logic would matter to more than one client, it probably belongs in a core service, not a BFF.

Pattern: Shared Libraries for Common Concerns Extract authentication, logging, error handling, and common utilities into shared libraries that all BFFs consume. This reduces duplication while maintaining the flexibility of separate services.

Pattern: Code Generation from Schemas Use OpenAPI, GraphQL schemas, or protocol buffers to generate BFF client code automatically. This ensures type safety and reduces the manual effort of keeping BFFs synchronized with downstream services.

Anti-Pattern: BFFs That Call Other BFFs BFFs should call core services, not each other. When BFFs start calling other BFFs, you've created a distributed monolith with unclear boundaries. Each BFF should independently compose data from core services.

Anti-Pattern: Business Logic in BFFs Resist the temptation to implement business rules in BFFs. Calculating pricing, enforcing workflow rules, or validating business constraints should happen in domain services. BFFs handle presentation concerns, not domain logic.

Anti-Pattern: One BFF per Screen Don't create a separate BFF for every UI screen or feature. Group by platform or broad user experience type. One Mobile BFF for all mobile screens, not separate BFFs for login, profile, and checkout.

Evolution and Alternatives

The BFF pattern exists within a broader ecosystem of architectural patterns addressing similar problems.

GraphQL as an Alternative For some use cases, GraphQL eliminates the need for BFFs by letting clients specify exactly what data they need. A single GraphQL endpoint can serve multiple clients, each querying for appropriate fields. However, GraphQL introduces its own complexity—query optimization, N+1 problems, and the challenge of implementing client-specific transformations server-side.

API Gateway with Transformations API gateways like Kong, AWS API Gateway, or Apigee can perform some BFF-like transformations—request routing, response reshaping, and aggregation. For simpler cases, this might suffice without dedicated BFF services. The trade-off is reduced flexibility and programming capability compared to full-fledged services.

GraphQL Federation with BFFs Some organizations combine patterns: each BFF exposes a GraphQL API that participates in a federated graph. This gives clients GraphQL's flexibility while maintaining BFF ownership boundaries.

Practical Considerations for Getting Started

Teams considering the BFF pattern should approach adoption incrementally.

Start with One BFF Don't migrate every client at once. Identify the client with the most distinct requirements—often mobile—and build a BFF for it. Validate the approach, refine operational practices, and build confidence before expanding.

Establish Conventions Early Define standards for authentication, error handling, logging, and monitoring before the second BFF ships. It's easier to establish conventions with one BFF than to retrofit consistency across five.

Invest in Observability With multiple services, comprehensive monitoring becomes critical. Distributed tracing (OpenTelemetry, Jaeger) helps track requests across BFFs and downstream services. Centralized logging and metrics ensure problems can be diagnosed quickly.

Plan for Common Concerns Decide upfront how to handle cross-cutting concerns: authentication, authorization, rate limiting, and API versioning. Shared libraries, service mesh, or API gateway integration can prevent each BFF from reimplementing these differently.

Consider Team Topology The BFF pattern works best with team structures that align ownership—"you build it, you run it" extended to both client and its BFF. If team structures don't support this ownership model, the pattern may introduce more friction than it resolves.

Conclusion

The Backend for Frontend pattern addresses a real pain point: the impossibility of serving diverse clients well from a single API. By introducing purpose-built backend services owned by client teams, BFFs enable faster iteration, better performance, and clearer boundaries.

But BFFs aren't free. They introduce operational complexity, potential duplication, and require organizational structures that support full-stack ownership. The pattern works best for multi-platform applications with distinct client needs, built by teams with backend capabilities, operating in microservices architectures.

For teams experiencing the pain of a one-size-fits-all API—where every change requires extensive coordination, performance suffers from competing constraints, and client-specific logic clutters shared endpoints—the BFF pattern offers a proven path forward. For others, simpler solutions like API versioning, feature flags, or GraphQL might better address their needs.

The key is recognizing that architecture isn't about adopting the latest pattern—it's about choosing solutions that match your team's capabilities, your system's constraints, and your users' needs. The BFF pattern is a powerful tool in that toolkit, effective when applied with intention to the right problems.

This post reflects common industry practices and architectural patterns observed across modern software organizations. The BFF pattern continues to evolve as teams discover new implementation approaches and combinations with complementary technologies.